A Shadowy Time

After tea’s introduction to England from China in 1660, those privileged enough to possess the herb were dedicated to the care of the leaf and preparation of the beverage, which was unaffordable to the average citizen. In the late 1700’s, tax on tea was greatly reduced and delivery of tea was expedited through speedy Clipper ships, making tea more accessible to the working class. The British craved tea and were resentfully dependent on China as their source for tea over several centuries. A shadowy period followed, involving the British trading Empire-grown opium to the Chinese for silver which was then used to purchase tea from China. This culminated in two Opium Wars, 1830-1842 and 1856-1860.

Following the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, the British East India Company sought to gain access to tea plants and seeds for the purpose of cultivation in the north of India, which they hoped would provide a source of tea to serve the Empire, independent of China. Fortune was an obvious choice for this undercover operation.

Fortune’s Journeys

“In these days, when tea has become almost a necessary of life in England and her wide-spreading colonies, its production upon a large and cheap scale is an object of no ordinary importance.” Ch 22, pg 394, A Journey to the Tea Countries of China, Robt. Fortune, 1858

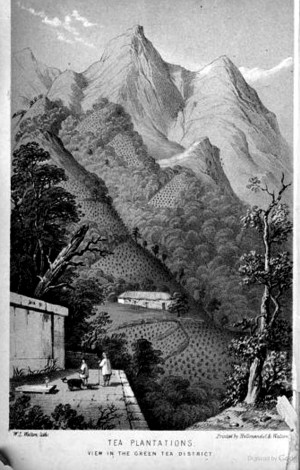

Starting from Shanghai and later the port of Ningpo, Fortune spent three years travelling through the interior of Fujian, Anhui and Zhejiang provinces, obtaining tea seeds, plants and skilled producers. No outsiders were allowed into the interior of China so he hid his British identity by disguising himself as a Mandarin with shaved head, braid and long robes. Travelling the rivers by junk and mountain trails in a chair, he experienced danger and excitement of the kind only found in books. Sensing that the public would be interested in reading about his journey, he published Journey to the Tea Countries of China in 1858. It was hugely successful and helped to bring him fame and financial security. Botanical specimens obtained on his journey were sent home for auction and provided considerable wealth for his growing family which remained in London while he was gone. His botanical ‘discoveries’ ensured his continued prestige, as many of the specimens were named after him.

Fortune used Wardian Cases to ship his tea seedlings to India. Invented by amateur botanist, Dr. Nathaniel Ward in 1829 to provide protection for his exotics from London’s heavy coal-polluted air, the cases proved ideal for the long journey of Fortune’s precious tea seedlings from China to North India. The modern day terrarium operates on the same principle, that a sealed glass enclosure will create its own ecosystem, allowing plants to thrive without additional water.

In the green house at Chelsea Physic Garden, a Camellia sinensis, sinensis plant can be found along with a reproduction Wardian Case. I’m sure though that the plant could easily thrive if planted out in the open air of the garden.

Rolling in His Grave?

Fortune made 4 visits in total to China. The first, on behalf of the Horticultural Society in Chiswick, London and the second for the British East India Company in 1848, while he was still Curator at Chelsea Physic Garden. He made two more trips to China (1853 to 1856) and (1858 to 1859) and one trip to Japan (1860 to 1862). He retired after his visit to Japan and spent the last eighteen years of his life in increasingly poor health at the family home at 1 Gilston Road, London SW where he died on 13th April 1880 aged 68. He is buried at the nearby Brompton cemetery.

Chelsea Physic garden has a charming cafe, Tangerine Dream, which was crowded on the day we visited. The tea was not memorable – I think it was a bag. Oh well. By now I was used to being disappointed with the quality of tea in England. The experience of tea time was always pleasant but the focus was definitely not on the leaves – the essence of the beverage, “pure and genuine as the Chinese drink it”.

Robert Fortune could never have imagined, as he peered through the mists of China, a vision of the 21st century British tea drinker, holding a corner of a paper tea bag over a mug of hot water and dipping it until it had produced the expected shade of brown. Thankfully, the reduction of tea to dust in paper, is slowly being replaced in Britain by a fresh appreciation for the whole leaf and its terroir. Seems to me that’s just a matter of respect for the man who risked everything for our love of tea.