Pargeters by Norah Lofts

My husband finds odd books in bins or at sales and occasionally comes home with some gems. Although he hadn’t read it, he thought I might enjoy a book called Pargeters by Norah Lofts, a prolific British author who wrote over 60 books. This was her last novel and it was posthumously published in 1984. The dust jacket was a bit faded and the cover illustration unsophisticated. 284 pages of historical romance in my hand with nothing much to recommend them. I was holed up in a cabin with few other choices so I opened it and launched in. At least it didn’t smell musty.

Pargeters of the title is an archaic English term that refers to skilled artisans known for fine plasterwork ornamentation on the exterior and interior of houses. (There is now a rockband, The Pargeters in Stourbridge UK). Lofts’ story is set in England’s Civil War which was fought throughout Britain over several decades. In the 1650’s setting of Pargeters, Oliver Cromwell, having abolished the monarchy, is about to become “Protector” of the new “Commonwealth”. Charles the First is executed. Brother turns against brother. Roundheads vs Cavaliers. It was a bloody and paranoid epoch. Still, in Norah Loft’s book, romance lives in hellish times. One Sarah Woodley Mercer fights to keep her family’s land and secretly supports the return of the Stuarts to the throne. She gets her delicate hands dirty by farming and marketing. She saves a royalist soldier (and falls in love with him). If she weren’t so self-denying we could compare her to Scarlett O’Hara.

This little novel was proving to be an amusing diversion and I was learning about social history during the mid-seventeenth century. Then I stopped in my tracks as I came upon page 145 which I share with you below. Narrated by the Sarah Woodley Mercer character. Remember this is 1650-ish.

“Mr Clover was in his study, a spacious room in the new outbuilt wing by incorporating, if I remembered rightly, part of what had been the old farmhouse kitchen. The walls were almost lined with books, with some new ‘scratch’ panelling between the shelves. There was a huge hearth with a good fire going on it, a new square-bowed window, with brown velvet curtains, looped back. In front of the hearth was a large, gaily coloured rug on which stood a settle, comfortably padded, a chair with cushions and a small table bearing some objects unfamiliar to me.

I took in all this detail while Mr Clover rose, greeted me, friendly but a trifle guarded, I thought and said, “Another cup, please, Mrs. Smith.” He indicated that I should sit in the chair, pulling it a trifle nearer the fire with a comment upon the unseasonable chill of the weather. “It is warm in here,” he said. “And a cup of tay will warm you still further. May I take your cloak?” He took it and hung it over the back of the settle while I wondered what tay might be.

Mrs Smith came in and set down the extra cup with such ill-grace that Mr. Clover said, “Gently. Gently! They are very fragile.”

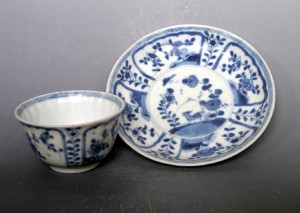

They were really small, shallow basins with matching saucer, and made of porcelain so fragile as to be almost transparent. They were beautifully painted, with small sprays of flowers which also decorated as much as I could see of the container, which was shaped rather like a pear, its lower half encased in a kind of basket work, very fine, and white in colour. The basket had a handle; the container a lid and a spout.

“It is an infusion,” Mr Clover said, lifting the container and pouring a pale amber liquid into the cups. There was a touch of ceremonial about the action, something that reminded me of Grandfather, in the old days, opening a bottle of wine which he thought rather special.

“I have never heard of it,” I said.

“I don’t suppose half a dozen people in England have. A colleague of mine at Cambridge has some connection with the East India Company, and obtained a small sample to try. He says it is the beverage of the future, having great medical virtues. It comes from China.”

I sipped. To me it was almost tasteless, and drinking it was difficult since the frail cup offered little protection from the scalding liquid. Mr Clover chatted on about tay, and China, and the East India Company; then the weather, his garden, some new bulbs he had ordered from Holland, almost as though he knew that I had come to him bringing trouble and he wanted to defer the mention of it for as long as possible. This gave me an opportunity to observe him and to wonder whether if it came to the pinch I could take Mr. Turnbull’s advice and marry him. I thought how amazed he would be to know that behind my wide-eyed attention I was assessing his possibilities as a husband.” (end of excerpt)

There are a few references that jump out at me. First is the shape of the cup “a small shallow basin”. This would be a tea bowl and probably unfamiliar if the English were used to flasks and flagons containing ale, which is what they mostly drank before tea came along.

In the 1600’s water was usually too unsafe to drink on its own. In fact, when tea became commonly enjoyed as a beverage, the grains used in the production of ale could be diverted for food uses. But I digress… the other thing I noticed was the use of the word “tay”. This was the correct term for the beverage at the time. Early European merchants came in contact with growers and traders from China’s Fujian province and this was their dialect’s pronunciation. It is still called “tay” in Ireland. And lastly “to me it was almost tasteless” – no doubt compared to wine or ale the green tea tasted very weak. It is likely that the green tea Mr Clover served was not as fresh as we would expect now. It had traveled months in a damp boat, sat in multiple docks for several weeks at a time, was warehoused and by the time it was consumed it had probably lost its vitality. It was most likely a Hyson or LuCha, generic terms at the time for Green Tea. Oolong tea had barely been discovered during this period.

British academics and botanists were becoming aware that China held riches, but were discouraged that it was largely impenetrable to outside forces. As the Ming Dynasty gave way to the Qing Dynasty (1660) England was finding its way back to stability and the Restoration of Charles II.

The simple reference to “tay” in Lofts’ novel inadvertently foreshadows the beginning of great social change in England. What may have seemed a bland liquid to poor Sarah Woodley Mercer would in Britain’s future become so valued that rooms in which “tay was taken” were designed and those “really small, shallow basins with matching saucers” from China influenced the beginnings of the British porcelain industry. The Chinoiserie decor that appeared a century later would have required the immense skills of the finest pargeters.